Mount Diablo Summit Building

by Linda Sanford

Reprinted from the Mount Diablo Review

April 1, 1998

Summit Building | Ruth Ann Kishi

The idea of having a museum or visitor center on the summit of Mount Diablo has been around for a very long time. In fact, even before Mount Diablo became one of California’s original State Parks those that visited the mountain top by stage, wagon and horseback commented on how great it would be to have a facility at the top of the mountain to interpret the spectacular view as well as the natural history of the mountain.

Mount Diablo became a park in 1921. Administered by its own Mount Diablo State Park Commission, it was one of seven state parks created before the establishment of the California State Park System. The first State Park Bond Act passed in 1928. It was primarily through local interest and extensive lobbying by local groups that 1500 acres came into State ownership as Mount Diablo State Park in 1931. Many of the local interest groups that had been formed to support the acquisition of the park continued to be active supporters of additional expansion of the park and construction of facilities. One common interest shared by all of the groups was the construction of an interpretive facility on the summit of the mountain. Although there was strong support from the Department of Parks and Recreation, the entire country was in the midst of the Great Depression, so little, if any, chance for public funds existed for such a facility.

However, while the Great Depression eliminated the possibility that the State would construct a mountain top visitor center, it also offered a unique alternative in the form of the federally funded Work Program Administration (W.P.A.) and the Civilian Conservation Corps (C.C.C.). Both of these programs put people to work and both programs were interested in constructing public projects such as parks, museums, roads, and public buildings.

In the mid 1930s the Department of Parks and Recreation entered into an agreement with the W.P.A. to complete sketches, drawings and paintings for pictorial histories of several State Parks for use in visitor centers and museums. Although Mount Diablo State Park did not have a visitor center of a museum at the time, it was included in the project. The plan was to complete the exhibits first and construct the facility to house them at a later date. Exhibits planned for Mount Diablo included the “scientific series” and “historic series”; each exhibit consisted of small panels in watercolor, gouache, pen and ink, or pastels. The artists and support personnel for the project worked in studios at the federal art project in the old Agricultural Department building, a converted school on Potrero Avenue in San Francisco.

An advisory committee was set up to assist the artists working on the projects. The committee consisted of a group of seven university professors to provide technical assistance and twelve local citizens from Contra Costa and Alameda Counties whose interest and influence in community affairs provided the necessary community support for the project. Dr. Bruce L. Clark, Professor of Paleontology at the University of California served as chair of the Mount Diablo Museum Project.

By 1938 enough displays had been finished to furnish the old single-story stucco building at the summit. The stucco structure was on the summit site at the time the park acquisition took place in 1931. In the meantime, plans for a permanent facility at the mountaintop were being developed.

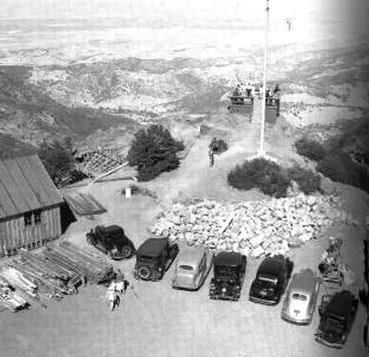

The new building was to be constructed by Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) personnel living at the CCC camp on the south side of the mountain. Company 2932-V (World War I veterans) started work on the summit building in 1938. While plans for the new observation building were being finalized, a number of older structures were demolished and the area prepared for the new building that would house not only a viewing deck but also an aircraft beacon, a fire lookout, and the museum exhibits. The new building was constructed from sandstone quarried at Fossil Ridge on the mountain. Standard Oil of California donated money for the mortar, steel, and other materials need to complete the structure.

Work on the new summit building came to a halt in 1940. The exterior of the building was completed, however, a serious problem with water leaks during storms developed during the winter months. Water would run through the mortar and sandstone into the interior of the building. Several attempts were made to solve the problem over the next several years. Although each solution helped, none seemed to totally resolve the problem.

In the early 1950s, the Department of Parks and Recreation obtained several contracts to seal and complete the exterior of the building. The mortar joints were sealed and pointed, the observation deck roof was resealed, Gunite was applied to the interior of the building and the exterior of the building was sealed. However, even this did not make the building entirely waterproof.

The work on the exhibits was completed by the W.P.A. in 1942 and the finished panels and displays were transferred to Contra Costa County’s Hall of Records for safe storage until the summit building was completed. When it became apparent that the leaks in the summit building would not be easily resolved, the displays were transferred to Mount Diablo State Park and stored at the recently abandoned Civilian Conservation Corps camp at Live Oak Campground. In 1951, after completion of additional efforts to seal the summit building, park employees discovered that many of the displays and paintings had been damaged beyond salvage by water, rodents, and dust. Those displays that could be salvaged were shipped to Sacramento where they were repaired and sent to other park units for use.

The final blow for the summit museum came in 1956 when the temporary museum caught fire and burned to the ground. The displays were lost as well. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s interest in a summit building visitor center continued to come to the forefront; however, without the necessary leadership nothing happened.

Then, in 1974, Mount Diablo Interpretive Association (MDIA) formed to promote public awareness of the cultural and natural history of Mount Diablo. The members developed a temporary visitor center in a portion of the old summit building, staffing it with volunteers and docents. As MDIA’s interpretive efforts grew they searched for ways in which the 40-year old dream of a museum and visitor center at the summit could be realized.

In 1982, the California State Park Foundation, a non-profit organization dedicated to expanding California’s parks and recreational opportunities, joined forces with MDIA to help raise the necessary funding for the summit building project. The next year, the Department of Parks and Recreation agreed to correct the water intrusion problem and prepare the structure for exhibits and displays. Daniel Quan Design of San Francisco developed the plans for the museum and visitor center. Installation of the exhibits was completed in 1984.

Today, the museum and visitor center house exhibits including a topographic model of the mountain. Rotating displays of art and photography complement the permanent exhibits. In addition to the exhibits, there is a small gift center within the building.

Outside the summit building, telescopes are mounted on the Mary Bowerman Interpretive Trail, a short walk away. On a clear day, the Sierra Nevada can be seen with the naked eye.

If you look carefully, ancient marine fossils embedded in the sandstone walls can be seen along the stairway walls leading to the observation deck. The rotunda on top of the summit building is a reminder of Mount Diablo’s importance as a survey point. Sitting atop the rotunda is the old navigation beacon, lighted once a year on December 7 in memory of Pearl Harbor.